historisches Zusatzmaterial zur Entdeckung von LDN (Interview Dr. Bihari)

Interview von Dr. Bihari über seine Arbeit mit LDN

Dr. Kamau B. Kokayi Interviews Dr. Bihari September 23, 2003 WBAI in New York City

“Global Medicine Review”

Orginal habe ich kopiert von http://www.lowdosenaltrexone.org/gazorpa/interview.html

Dr. Kokayi: …the story about Low Dose Naltrexone is really fascinating. How did you get the idea?

Dr. Bihari: Well, we were treating heroin addicts, and in 1984 a new drug for the treatment of addiction came out. It was called Naltrexone, and it was designed to block the heroin “high”and it was a flop. I used it for a lot of patients, as did most addiction doctors across the country. At 50 milligrams a day, it made people feel terrible. Not that it blocked the heroin so much as it blocked their own endorphins, which is a source of our sense of well-being, so that people couldn’t sleep.

Dr. Kokayi: Your own opium, basically.

Dr. Bihari: Right. Your own equivalent. That’s what heroin is. And I knew from work that had been done by the National Institute on Drug Abuse in developing the drug that it had the ability to trigger the body into making more endorphins, but at the high 50 milligram dosage, the dose was too high. It blocks those endorphins.

About six months later our addicts began dying in large numbers of AIDS. I ran HIV tests on about a hundred addicts, and fifty percent were already HIV positive. This was in 1985; currently it’s eighty eighty-five percent around the country. And we began looking for some way to approach this new disease, with a view to the idea that this disease was likely to turn into a worldwide epidemic.

Dr. Kokayi: That was about the time where people were just being blasted with AZT with horrific results.

Dr. Bihari: Right. There was nothing else available. When I discovered that people with HIV had less than twenty percent of the normal levels of endorphins, that meant that the virus not only kills the immune system cells, it also weakens the whole immune system, so that it’s not as able to fight the virus.

We began looking for ways to use this drug to raise endorphins without blocking them. We hired a laboratory scientist to measure endorphin levels. We’d measure in the afternoon, then we’d give the first dose at bedtime that night. Then we’d measure again at the same time the next day; then again at one week, and again at one month. We found that doses in the range of 1.75 to 4.5 milligrams (which is just a fraction of the recommended dosage to addicts) would trigger or jumpstart endorphin production during the night.

Except with exercise, endorphins are made only between two and four in the morning. The brain sends a message out to the adrenal and pituitary glands and tells them to make endorphins. Giving a dose three, four, five hours before that, at bedtime, is enough to make that message from the brain much stronger.

Dr. Kokayi: Were you able to document that the levels of endorphins were then actually raised?

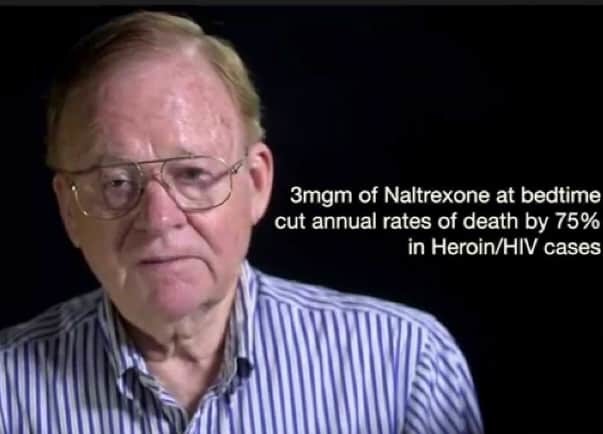

Dr. Bihari: The level of endorphins went up by two hundred to three hundred percent. We then started a little foundation and did a placebo-controlled trial in which half the patients got the drug and half got sugar pills. A year later when we broke the code, we discovered that people with HIV who took the drug had only an eight percent death rate in the year, while people who were on the placebo had a thirty-three percent death rate. And of course they had many more infections and their immune system declined. That was a startling discovery.

Dr. Kokayi: Now let me jump ahead, because I’m always curious about why this therapy hasn’t gotten the kind of publicity specifically for this disease.

Dr. Bihari: Well, at that time there was very little treatment. AZT came out about ’87, and as you mentioned, it was not only a flop but made some people sicker. At the time we did the study, there was nothing available.

So I met with doctors in New York and in San Francisco (where the largest number of HIV doctors were at that time) and described this drug and how it worked, and about forty to fifty doctors on the east and west coast began using it. Unfortunately, they measured effectiveness by whether or not the numbers of the immune system cells that are crucial in AIDS — the CD4 cells — were rising. On this drug, CD4 cells don’t rise in people with AIDS. As I knew from the study, and have known since, they simply stop dropping. That means you can freeze the disease wherever it is. And if somebody is only mildly immune-suppressed, they stay that way.

Dr. Kokayi: That’s so important…

Dr. Bihari: It stops progression. It stops the count from growing. I have patients going back as much as seventeen years who haven’t lost an immune system cell in that time. They’re very healthy.

Dr. Kokayi: Wow, that needs to be on the evening news.

Dr. Bihari: The trouble was, we wrote a paper, but couldn’t get it published. Nobody understood the concept.

Dr. Kokayi: You’re using the dose homeopathically. You’re using it not for the effect that the medicine has on the person, but for the body’s reaction to the medicine.

Dr. Bihari: It strengthens the body’s own defenses. Rather than directly attacking, the way antibiotics attack bacteria, or the way chemotherapy tries to attack cancer cells, or the way anti-viral drugs attack viruses, the purpose of this is to take a weak defense (which people with AIDS or cancer have), and strengthen it so that the body can fight the disease more effectively.

Dr. Kokayi: I’ve often made the point that therapies like acupuncture, therapies that are foreign to the cultural mindset of doctors and the American public, these therapies can be effective, but they won’t be included or in mainstream medicine because the concept is so foreign.

Dr. Bihari: It’s a different model of understanding the body — how it works and how disease works. I think eventually there will be changes in the paradigm of the way we think about diseases, and it’s going to be a struggle. But I think oncologists in particular are getting more and more frustrated with the failure of chemotherapy.

Dr. Kokayi: Well, about time.

Dr. Bihari: The people I talk to at the National Cancer Institute, and the Food and Drug Administration, are very negative. All they get from drug companies are proposals to test new, more toxic chemotherapies, and they’re really looking very hard for non-toxic ways of modifying the behavior of the cancer cells so that they stop the cancer from growing.

Dr. Kokayi: Over the years have you had to modify what you were actually doing with Naltrexone? Or is the initial model impetus pretty much on point?

Dr. Bihari: The initial model was pretty much on point. A small dose at bedtime increases endorphin production during the night. In somebody who has a disease which is related to low endorphins, the endorphins go back up to normal by the next day.

… [station break] ….

Dr. Kokayi: … can you tell us about some of the work with Naltrexone and cancer?

Dr. Bihari: During that year, when we were doing our first AIDS trial, an old friend of mine called. Five years earlier, she’d had Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. It had initially responded to chemotherapy, but it had grown back after her husband died. Her oncologist refused to treat her, saying it would be resistant to chemo the second time.

She knew what I’d been doing, and she called me and said, “Bernie, do you think your AIDS drug would help my cancer?”

So I dug around and I found a large body of literature showing that when you give endorphins, metenkephalins, beta endorphins and even low dose Naltrexone to mice that had human cancer transplanted, that there is about an 80 percent recovery rate. I gave her the drug in the same dose we were using in the AIDS trial. She had large masses in her groin, her neck, her chest, and her abdomen, and they all slowly shrank and disappeared over a (inaudible) period. (Inaudible) taking the drug every night.

Dr. Kokayi: Wow! You know, even if that’s just an anecdote….

Dr. Bihari: Yes.

Dr. Kokay: I mean, everyone who has that disease deserves a chance to see if they’re going to be an anecdote as well.

Dr. Bihari: It was actually her idea. She stayed on the drug, and died about eight years later, in her late seventies, of her third heart attack, which was unrelated.

Then I was in Paris the following summer, presenting a paper at an AIDS conference, and I met a woman who had a cancer called malignant melanoma. It starts in the skin, and in her case it had spread to the brain. She had four large brain tumors. The oncologist told her family that she had perhaps three months to live. When I got back to New York, I shipped her the drug from a pharmacy that was making it for our study. She started on it, and her neurological symptoms from the tumors in her brain slowly disappeared. Seven or eight months later she went back to the oncologist, had a cat scan of the brain done, and the tumors were gone.

Dr. Kokayi: Fantastic.

Dr. Bihari: That was eighteen years ago, and she stayed on it.

Dr. Kokayi: This is such a non-toxic, simple [inaudible].

Dr. Bihari: There are absolutely no side effects. I continued doing a lot of the AIDS work, but the last four or five years I’ve gotten much more interested in other uses. We stumbled on the fact, also by chance, that the drug works very well for almost all, if not all, of the autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, sarcoidosis, and —

Dr. Kokayi: When you say “it works”, what actually happens? What’s been your experience?

Dr. Bihari: Well, what happens is that the disease activity stops, as long as people stay on it. If they have damage to the brain and spinal cord with multiple sclerosis, that doesn’t disappear, because that’s due to scarring, but they stop getting new attacks.

I’ve had people on Low Dose Naltrexone for years. The longest is a friend of my daughter, who’s been on it for eighteen years and has not had an attack as long as she stayed on it.

Dr. Kokayi: So it’s almost as if it’s up-regulating the endorphin production but somehow the endorphins actually block or inhibit the effect of the antibodies from attacking the tissue.

Dr. Bihari: Not directly. It’s more that the autoimmune diseases are beginning to look more and more like they’re diseases of endorphin deficiency. [Inaudible] models of all the diseases I mention that can be bred in mice, the endorphin levels are always fifteen to twenty percent of normal compared with normal mice.

[Female Voice] How can you naturally increase endorphin levels?Dr. Bihari: There’s only three or four ways that I know. First, Naltrexone increases them substantially, two to three hundred percent in people with low levels. Second, aerobic exercise increases them, but not as much. If you do an hour of exercise four or five times a week it will last three, four hours, and that’s one of the reasons that exercise helps prevent cancer. A third way, oddly, is acupuncture. Acupuncture, especially when used in treating addicts, increases endorphin levels in the blood and the spinal fluid. And chocolate increases it.

Dr. Kokayi: [Inaudible] will be glad to hear that.

Female Voice: [inaudible] It actually works out, because you’re going to eat your chocolate and then run to the gym.

Dr. Bihari: Chocolate has a substance in it called Phenylalanine, which slows endorphins from being broken down in the body.

Dr. Kokayi: And that’s basically an amino acid that we find….

Dr. Bihari: Yes, that’s the food that has it in the largest amount. And only people with a rare disease called [inaudible] can’t eat chocolate.

Dr. Kokayi: So some people will run to the health food store and get Phenylalanine.

Dr. Bihari: Well, Phenylalanine is helpful if you’re raising your endorphins by other means. Then it keeps them from decaying. They last much longer. But the crucial thing still seems to me to be the Naltrexone. Over the last five or six years, I’ve treated about 420 patients who have various kinds of cancer with low dose Naltrexone. Occasionally, for people who come to me with very advanced cancer, I add intravenous metenkephalin, which is an endorphin… intravenously, three times a week. It improved immune function substantially, and had no side effects, but that’s generally not needed.

Among the people I’ve treated with Naltrexone for various kinds of cancer, on the average the cancer stops growing in about two-thirds. For half of that group, it eventually — after six, seven, eight months — goes on to slowly shrink and disappear.

Dr. Kokayi: And that’s about forty percent.

Dr. Bihari: Higher.

Dr. Kokayi: Well, it’s about forty percent of the total number.

Dr. Bihari: Sixty-five percent actually benefit and don’t go on to develop [inaudible]. Thirty percent go into remission.

Dr. Kokayi: That’s phenomenal. I don’t think there’s any chemo or radiating oncologist with numbers like that.

Dr. Bihari: There’s no downside. One of the reasons that the war on cancer failed is that the oncologists doing the research failed to take into account that chemotherapy really wipes out the immune system, which the body needs to fight cancer cells. So they are giving drugs that kill cancer cells, but at the same time weakening the body’s defense against cancer. Naltrexone strengthens the body’s defense, and the increased endorphins kill cancer cells directly. Also, the immune system when it’s strengthened kills cancer cells through its natural killer cells.

Dr. Kokayi: What you’re saying is, that a boost in endorphin levels also activates other components of the immune system.

Dr. Bihari: The endorphins are the hormones centrally involved in regulating the immune system. About 95% of the regulation or orchestration comes from endorphins. People with cancer — especially adults – have very low natural killer cells. They have a weakened immune system. I’ve discovered, after seeing such a large number of people, that the vast majority of them have experienced major life stresses lasting weeks, months to years – anywhere from two to six years before they get the cancer.

Dr. Kokayi: That was one of my other questions. What really can keep those endorphin levels down in the body?

Dr. Bihari: If a child gets sick — children are supposed to outlive us — so if a child gets sick and dies, or if you have a very bad marital break-up, or if you discover a business partner is embezzling money and it takes a couple of years to straighten out… If you wake up every morning under stress — really serious stress, not everyday stress — really serious stress, this can lower your endorphin production, and it never returns to normal. So the person then walks around with low endorphins. The body makes cancer cells all the time, but usually the immune system kills them as they are forming. But if your endorphin levels are low, then your immune system is weak, the cancers grow and you become much more vulnerable. The same thing with exposure to really toxic substances.

Dr. Kokayi: Right. I’m wondering, I’m sure the listening audience would like to get an idea. If you could just run down a list of some of the cancers that you have successfully treated, types of cancers that have seemed to respond where the opiate levels play a prominent role.

Dr. Bihari: Well, first one of the things we discovered was that almost all cancers have a lot of receptors for endorphins on the cell surface, and that seems to be necessary for it to work. Some of the cancers that respond most dramatically are Multiple Myeloma, Lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, breast cancer, all the cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, like pancreatic cancer, non small-cell cancer of the lung, the kind associated with smoking. I’ve got several patients with tumors that have stopped growing; they have no symptoms, and then after a year, year and a half, in about half of that group, the tumors start shrinking and disappear.

Dr. Kokayi: This is lung cancer?

Dr. Bihari: These are lung cancers due to smoking.

Dr. Kokayi: Because there’s really —

Dr. Bihari: Very common.

Dr. Kokayi: It’s very common, but therapeutic effectiveness —

Dr. Bihari: There’s nothing —

Dr. Kokayi: There’s nothing, right —

Dr. Bihari: My own attitude about chemotherapy in patients I see with cancer, is if they have one of those rare cancers that’s very sensitive to chemotherapy, like cancer of the testicle, I encourage them to do that, to take it, and take Naltrexone afterwards to prevent recurrence. These drugs are licensed to treat cancer. Naltrexone is not yet licensed to treat cancer, although it’s a licensed drug. It’s been on the market for nineteen years. It’s use in these low doses is called an “off-label” use. Any doctor can prescribe it. And growing numbers of oncologists and neurologists in the country are prescribing it.

Dr. Kokayi: I think it would be interesting you know just to talk a little bit about the process … a lot of physicians don’t really know about it and it’s not talked about. This is a big deal.

Dr. Bihari: Well, I think it could turn out to be a big deal when it’s picked up, if it’s picked up. We set up a web site, www.ldninfo.org, which brings up about thirty pages of written material describing all the diseases, and how they respond, and how many cases we have of them. There’s some small trials going on, there’s two trials in people with Crohn’s Disease, which is an autoimmune disease of the small intestine, one in Jerusalem, and one in New York. There’s a trial in Israel for multiple sclerosis. The national cancer institute has copies of twenty charts of my patients who have agreed to share their charts. These are people who have done well on Naltrexone when nothing else could explain how well they’ve done. They intend to present them to a committee for recommendations as to whether to invest and test it in the network of cancer research.

Dr. Kokayi: You know, when I think about Africa and AIDS, this is exactly the kind of medicine there needs to be there….

Dr. Bihari: This is perfect. In fact, we’ve been working with the largest pharmaceutical company in the developing world called (inaudible) in India to get a trial going, probably in Africa, in the Republic of South Africa, in which half the HIV patients get the drug, half get a placebo, and they should be able to show in about nine months, using two to three hundred patients, that this drug stops progression.

Once it does, it will be manufacturable at less than ten dollars per year per person. That’s been the big problem — the anti-HIV drugs are so expensive. The average income in Africa is about eighty dollars per year.

Dr. Kokayi: I can only imagine just the financial stress that you’ve had to go through just to keep this whole project alive. It’s one thing to prescribe things as an individual doctor, but to get recognition within the scientific community is a bit difficult.

Dr. Bihari: It really bothers me when doctors say, “Oh, I can’t prescribe that, because he hasn’t done a placebo-controlled trial.” That’s a full-time job, for two, three years involving eight or nine centers around the country. I’m working with a number of diseases in my office, and a lot of money goes out paying for the website, for patents to cover low dose naltexone, and (inaudible) things like that. It’s very veryexpensive. But I can’t stop doing it. My wife and I would love to do some traveling — I think we’ve earned it — but I really can’t stop until the drug is out there. It’s as much of a burden as it does a pleasure.

Dr. Kokayi: I really hope that at least your sharing with our listening audience today helps to make people more aware. People should be clamoring for it. We’re running out of time, but I wanted to go back to the treatment of autoimmune diseases. I always pictured them as the body is attacking its own tissues. I pictured these antibodies actually honing in there. But you’re saying that, in large measure it’s an actual endorphin deficiency.

Dr. Bihari: It’s an endorphin deficiency which weakens the immune system, so that certain cells in the body forget to distinguish between the body tissues and bacteria or viruses, so when these cells are activated by an infection they attack the bacteria and they attack you. Restoring the immune function to normal stops that. So far, the drug works dramatically in all the diseases that are labeled autoimmune diseases.

Dr. Kokayi: And you’ve treated lupus with this.

Dr. Bihari: I’ve treated — I have two dozen cases of lupus. I have about the same number of people with rheumatoid arthritis. I have about twenty people with Crohn’s Disease. A number of rheumatologists who specialize in these diseases in New York are now beginning to use it, because we have cases in common, and they see.

Dr. Kokayi: Right

Dr. Bihari: Because they’re using cancer drugs

Female Voice: Dr. Bihari, is this being used with children with ADD?

Dr. Bihari: I doubt that it would work, knowing the nature of ADD. I doubt that it would work. It doesn’t do everything for everybody. I don’t think it would.

Dr. Kokayi: Again, going back to the idea of giving a medicine that at a higher dose actually blocks the chemical system, but a lower dose actually augments it.

Dr. Bihari: And enhances the body’s defenses — that’s essential.

Dr. Koyayi: This idea gives the pharmaceutical industry something to do, rather than giving people high doses of medication.

Dr. Bihari: It certainly would. It will take this drug to be licensed, picked up by a pharmaceutical company and tested, licensed, and once it’s widely used, then this approach to medicine — every medical researcher will start thinking about it. It’s an entirely different approach to the body and illness.

Dr. Kokayi: What is the next step? Is there anything that the listening audience can do that might be helpful for to make this more — not even make it more available, because it’s just a prescription any doctor can write. I guess it’s the information —

Dr. Bihari: The information, getting it from the website, getting doctors to prescribe it. I’m always happy to take calls from doctors and spend as much time as I need, because the more doctors prescribe it, the more widely used it will be. Currently, as far as we can calculate it, over eighty thousand people in the U.S. and western Europe are on the drug, and the numbers are increasing rapidly.

Dr. Kokayi: I’d like you to give your website one more time and the number where people can reach you …

…

Well with that, thank you again and I’m sure we will be talking to you again soon.